YouTube / BFBS Creative

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, several aircraft companies separately decided to test the viability of vertical or short takeoff and landing. The concrete runways were vulnerable to attack, so the solution was to make an aircraft that could take off from virtually anywhere.

But making a jet hover is easier said than done. Jets fly because of the air passing over their wings, and with no forward momentum, it just doesn’t work. The key was downward thrust – just enough to lift the entire plane.

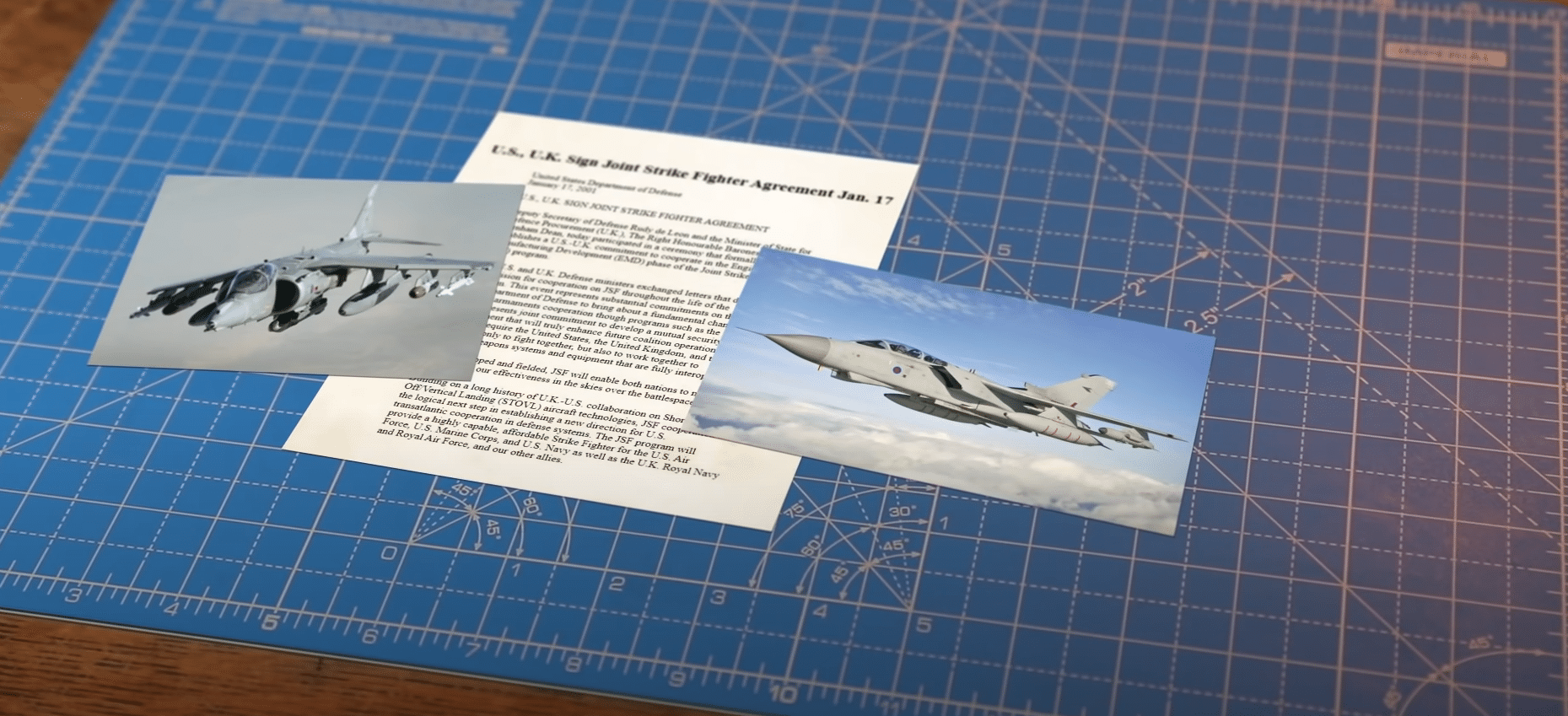

Of the dozens of designs from several decades, only the Harrier and the YAK-38 reached operational status. Still, prioritizing the ability to hover meant the Harrier had to sacrifice in other areas. It couldn’t fly at supersonic speeds nor carry as much fuel or munitions as other fighters.

In 1993, the US started the development of its Joint Strike Fighter Program. They were looking for a new fighter to replace the F-16, A-10, F-18, and AV-8Bs. Two years later, the UK would become a formal partner, signing up to buy the aircraft to replace their Harrier and Tornado.

This proved to be an arduous task since the aircraft had to fill many holes left by several aircraft retirements. To be viable, it needed to fly at supersonic speeds, have stealth capabilities, and have the ability to take off and land vertically.

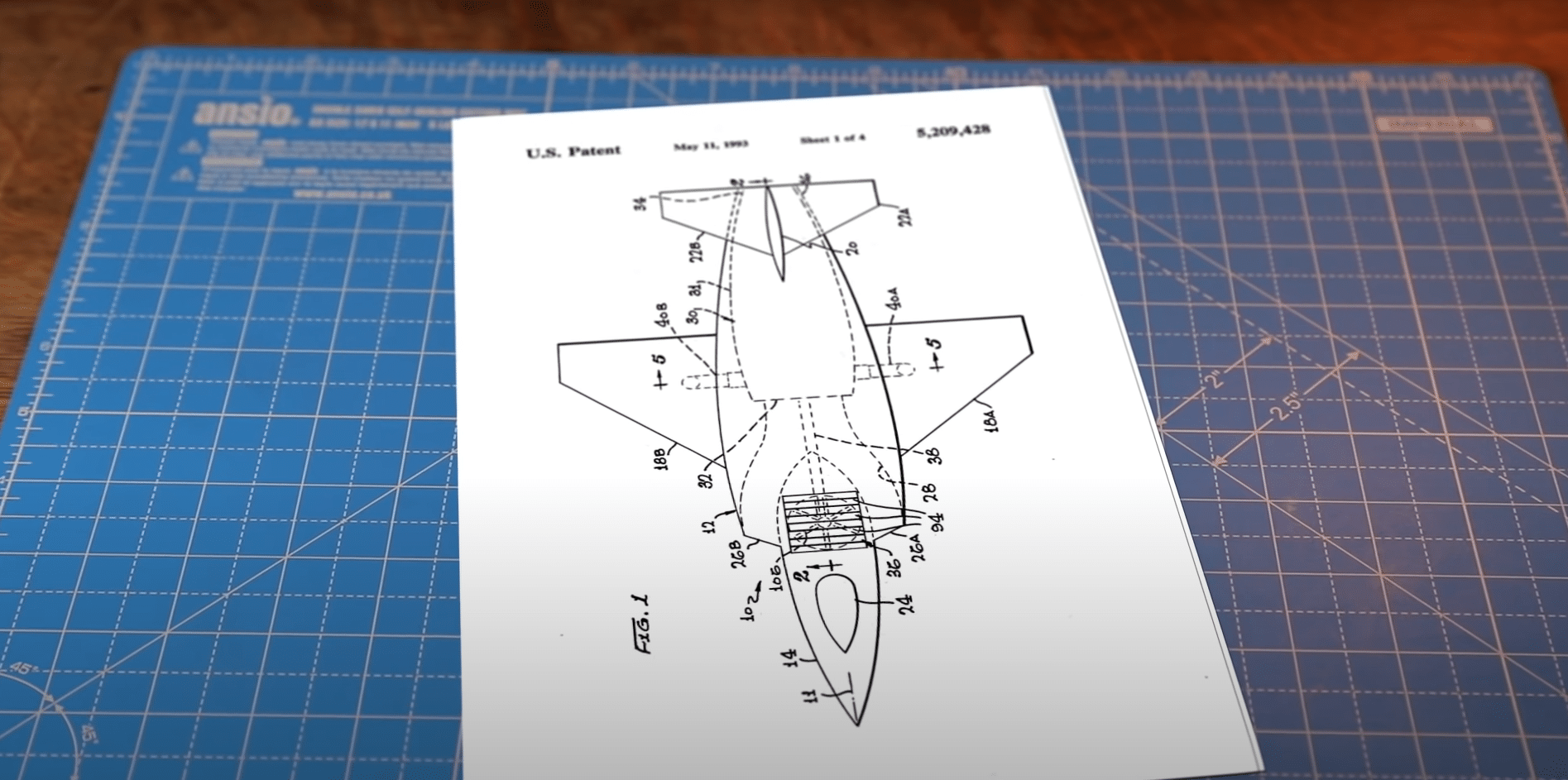

However, Skunk Works had already found and patented the perfect answer years earlier.

Their solution was a lift fan inside the fuselage, just behind the pilot. Where the Harrier has its rotating nozzles for downward thrust, the F-35 uses a combination of an internal lift fan and rotating its main engine nozzle at the back so that it’s pointing downward.

Combined, the fan and nozzle produce more than 40,000 lbs of thrust. The lift fan was the only solution to appease the program’s requirements. And just like that, the F-35B became Britain’s next hover jet.